1948 Rose Bowl

The 1948 Rose Bowl and the Most Pivotal Moment in Michigan Band History

By Joseph Dobos ‘71

In the fall of 1947, the University of Michigan football team won nine consecutive victories, including four shutouts, and earned their first outright Big Nine conference title since the National Championship season of 1932. It was Fritz Crisler's tenth year as coach at Michigan. Beginning in 1946, the Big Nine Conference and the Pacific Coast Conference had an agreement for their respective conference champions to meet on New Year's Day in the Rose Bowl in Pasadena. Thus, on January 1, 1948, the University of Michigan Wolverines met the Trojans from the University of Southern California and won with a score of 49-0. It was the second time that Michigan had played on New Year’s Day since the first Rose Bowl in 1901. At that time, Michigan defeated Stanford by an identical score of 49-0.

For the University of Michigan Marching Band, the 1948 Rose Bowl marked the band's first appearance in a postseason game. And it was the first time that any Michigan Band had performed in the western part of the United States. While this is an extraordinary story in itself, the 1948 Rose Bowl performance is part of a chain of events that took place during the 1947-1948 academic year—events that dramatically changed the style and the image of the University of Michigan Marching Band. What is more, it would be the most significant year of William Revelli's career at Michigan.

Thanks to the G.I. Bill—the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act—the fall of 1947 saw the first significant influx of students to the University of Michigan thanks to the granted stipends that covered tuition and expenses for veterans attending college. While colleges everywhere experienced a rise in enrollment, a prime destination for these returning G.I.'s was the University of Michigan, and this had a direct impact on the University of Michigan Marching Band. The 1947 Marching Band was the largest in its history to date. Over 230 men competed for the 131 available positions. Of the band's 131 members, 65 were students at the School of Music. More than a dozen were graduate students.

The makeup of the band reflected the University’s post-war student enrollment. More than half of the men were veterans of the war. Many were married. Many had children. Many had seen battle during the war. Revelli’s legendary rehearsal temper seemed pale compared to what they had experienced during the war. At worst, Revelli reminded them of “an overbearing drill sergeant.” Years later, Revelli admitted that he learned to treat these men differently than the way he had dealt with students in the past. For one thing, these older men thirsted for knowledge and actively wanted excellence. Revelli discovered that they were willing to do anything he asked of them.

In 1947, the University of Michigan Marching Band attracted so many returning veterans because it was unique among college bands. During the war years, most college bands dissolved. The University of Michigan Marching Band was one of the few college bands that never ceased operation. When the war ended, most college bands had to start up from scratch. In Ann Arbor, Revelli's bands were ready to go the minute the war ended. For the G.I.’s and others, the Michigan Band was a destination of choice.

During the war, many ROTC musicians were stationed in Ann Arbor. They were impressed by the School of Music and the campus. After the war, they were eager to return to Michigan. While some students came to Michigan because of the reputation of William Revelli, this was not true of everyone. Typical of this latter group was George Cavender. Before the outbreak of the war, Cavender had been a high school band director in northern Michigan for one year. When war broke, out Cavender enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps. When the war ended, he was discharged and decided to take advantage of the educational opportunity of the G.I. Bill. He chose the University of Michigan to pursue his graduate degree in Music Education. He did so not because of Revelli but because of the reputation of the School of Music and the University. Cavender claimed never to have heard of Revelli before coming to Ann Arbor. He said, "The first time that I knew of Mr. Revelli was when I attended my first rehearsal of the Michigan Band. When I was in high school and college, Glenn Cliffe Bainum was the university band director that I knew and admired.”

The stability of the post-war Michigan Band was due to several factors most important of which was the vision and leadership of Alexander Ruthven, the President of the University of Michigan. Ruthven had been associated with the University since 1906—first, as a graduate student, then, as a member of the faculty, and eventually, President of the University.

It was as a faculty member when Ruthven had seen, first hand, the disruption to the academic mission of the University that took place on campus at the outbreak of the American involvement in World War I. By 1918, most of the University ceased operation. Many faculty members lost their jobs including Wilfred Wilson, the Director of the University of Michigan Band. With no teaching position, Wilson was forced to leave Ann Arbor to seek employment elsewhere. For a time, he worked on the family farm in Indiana. Later, he served as an instructor of brass instruments at the U.S. Naval station in Waukegan, Illinois where he met John Philip Sousa.

In the early months of 1941, Alexander Ruthven ordered all departments to come up with a plan to convert the University into a center of training for military and civilian personnel. Foremost in Ruthven's mind was that when war broke out, all the resources of the University of Michigan would be devoted toward winning the war. At the same time, the integrity and mission of the University had to be preserved. The mistakes of World War I would not be repeated.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor and the declaration of war, the University of Michigan, alone among all colleges in the country, was immediately ready to convert all programs for the cause of the war effort. Curriculum instruction was adapted and accelerated so that students could graduate in two and a half years. Every department on campus had a modified curriculum to provide a first-rate education and, at the same time, offer vital service to the country. In areas of scientific research, medicine, language, engineering, and law, the U.S. Pentagon considered the University of Michigan to be indispensable to the war effort. By 1943, there were more than 4,000 men in uniform stationed at the University. Also, there were more than 6,500 civilian men and women working and studying on campus. Dormitories and fraternities were taken over to house the military and civilians.

With the arrival of so many military personnel came the need for military bands on campus. William Revelli and the University of Michigan Band were "ordered" by Alexander Ruthven, and indirectly by the U.S. government, to retain a viable and active musical presence. Since 1928, the University of Michigan Marching Band was organized and drilled by an officer from the ROTC. This proved to be a useful connection between Revelli and the newly created bands for the Naval and Army ROTC bands. Revelli was charged with the continuation of the University of Michigan Band as well as assisting the ROTC bands. There were about 100 men in the Naval-Marine ROTC Band and about 40 men in the Army ROTC band. The membership in these bands was comprised mostly of musicians who had not been at the University before. Overseeing the three band programs meant more work for Revelli. While Revelli, himself, did not conduct the ROTC Bands, he trained and advised personnel who did. Many men were members of an ROTC band and the regular Michigan Band. But the real challenge was to keep the Michigan Marching Band functioning. The coming and going of students meant that the membership of the Michigan Marching Band was in constant flux. As the draft expanded, this affected the regular students who were in the traditional Michigan Band which had only 48 men with which to operate. Years later, Revelli would say that "students were leaving school like flies.” The war affected the status of faculty members, too. From 1943 to 1946, Revelli’s right-hand man in the School of Music Wind Instrument Department was William Stubbins. He, also, left the University to serve in the U.S. Navy as a lieutenant in the Pacific Theater.

On orders from President Franklin Roosevelt, collegiate football continued during the war. The marching band that Michigan fans saw on the field at the football games was a combination of the ROTC bands and the Michigan Band. By agreement of the commanding officers on campus, the ROTC bandsmen were allowed to wear the University of Michigan uniform on the day of the game. Because of other duties, the ROTC bandsmen were released from duty for only one marching band rehearsal per week which took place on the Friday night before the game. Revelli went to great lengths to arrange and simplify the music and formations so that the "Michigan Marching Band" would sound good and look sharp. Revelli avoided intricate marching and played music that was accessible. On football Saturdays, what the crowd saw and heard in Michigan Stadium was a large marching band that looked like and had the polished sound of a Revelli band. Unknown to the public, it required much effort on Revelli's part to make this happen. The press and radio announcers noted that while other university marching bands had dwindled, or ceased operations altogether, the Michigan Band seemed to be flourishing. What the public did not realize was that, during the war years, several hundred students passed through the Michigan Band each year. Some men were only in the Band for a few weeks. As one Michigan Band alumnus recalled, "The guy marching next to you, one week, might be gone the next." Members of the band—whether they were long-term or just temporary—were proud of the fact that they kept the Michigan Band intact. In a letter, dated January 6, 1945, Mac Carr expressed the pride that school band directors in Michigan had for Revelli and his efforts to keep the Michigan Band afloat during the war years.

Post War—A Time of Many Changes and Growth

“With the return of peace, the University shook itself loose from wartime restrictions and objectives. The special classes melted away, and the scattered faculty members returned to campus.” It was the genius and foresight of Alexander Ruthven that transformed the University of Michigan into one of the country’s most valuable assets for the war effort, and after the war, it was Ruthven's leadership that returned the University to its regular campus life.

When the war ended, Revelli was able to dissociate the Michigan Band from the ROTC program—something he had wanted to do since coming to the University in 1935. Earl Moore approved of this move and allowed Revelli to create a new position of Assistant Conductor of Bands. Harold Ferguson was hired to be Revelli’s assistant and had the responsibility of creating shows and maneuvers as well as all aspects of rehearsal on the drill field. Ferguson also was also appointed instructor of low brass at the School of Music. Harold Ferguson came to the University with a statewide reputation as an expert on marching bands. His accomplishments as a band director at Lansing Eastern and Lansing Sexton high schools were widely acclaimed. With his own handpicked assistant and with connections to the ROTC severed, Revelli said, “At last, I had complete control of the band.”

The post-war Michigan Marching Band reflected the expertise of Harold Ferguson's leadership. The band performed with drills of intricate detail. But, it continued to march in its traditional ROTC military 30-inch step—marching six steps to 5 yards. Because of the large step, tempos had to be moderate.

November 22, 1947, proved to a pivotal date for William Revelli and the University of Michigan Marching Band. It was the annual football clash between Michigan and its arch-rival, Ohio State University. Before a capacity crowd of nearly 86,000 in Michigan Stadium, the Wolverines crushed the Buckeyes by a score of 21-0. In so doing, Michigan earned an invitation to play in the Rose Bowl on New Year’s Day. But on that cold Saturday in November, the Michigan Band lost the battle of the bands.

At halftime, the Ohio State University Marching Band took the field, first. After the war, the director of the OSU Band, Manley Whitcomb, and a group of his students, decided that it was time to change the image and style of the OSU Marching Band. They shortened the marching step to 22 1/2 inches enabling bandsmen to march eight steps to 5 yards. This change better matched the phrasing in the music. Also, the shorter step allowed for an increase of the tempo up to 180 paces per minute. Adding to all this was a high knee and leg lift which added to the spectacle. Wearing shakos, scarlet cross-belted uniforms, and white spats, the OSU Marching Band presented a fresh and exciting image. Whitcomb replaced the traditional military marches the band had typically played with popular songs and humorous gimmicks. The innovative and fast-paced show of the OSU Marching Band caught the imagination of the Michigan crowd, and it gave the band a cheering standing ovation when they left the field.

Then followed the Michigan Marching Band. Its uniforms looked outdated and drab. Its marching pace was slower as it used the traditional military stride. The Michigan Band presented a show entitled The Great 1947 Football Team which seemed dull in comparison to the OSU Band show. The Michigan Band’s drill consisted of a quick sequence of word formations spelling the nicknames of the ten senior football players playing their final game in Michigan Stadium along with words such as TEAM and MICH. When the Michigan Band left the field, there was little applause from the home crowd. Revelli thought he even heard some booing. He was embarrassed and angry. Not since his first year in Hobart had he come in “second” in anything.

Michigan's victory over OSU ensured a trip to Pasadena, and the Michigan Marching Band would be present at the game courtesy of a $30,000 gift from the Buick Motor Company. (In today's money, that would amount to a gift of $337,000.) Revelli decided that the Michigan Band had to change its marching style for the all-important appearance in the Rose Bowl on January 1st. He ordered Harold Ferguson to teach the Michigan Marching Band how to march in the new manner that the Ohio State Band had used.

During the weeks after the Ohio State game, it was too cold to practice outdoors. The only place large enough was "Hanger No. 2” at the University of Michigan's Willow Run Airport in Ypsilanti. There, the Michigan Band learned to march with a high step with a much faster tempo than had been used previously. But they did so with the traditional 30-inch military step and not with the shorter 22 1/2-inch step that the OSU Band used. There wasn't enough to time make the change. The result was a fast-paced, high stepping band that looked awkward and was difficult to execute.

As the band worked hard to learn this new style of marching, Revelli added to the stress of the moment. He cautioned the men that if the “up tempo-modern style in any way caused a deterioration of the sonority of the band,” he would drop back to a slower cadence which would have them sound “the way a Michigan Band must sound.”

On Christmas Day, the Michigan Marching Band began its journey to California by train. Along the way, there were stops in Denver, Salt Lake City, Kansas City, San Francisco, and several small crossroad towns. In all these places, the routine was the same. The band would depart from the train and parade march through the city to a field where they could rehearse. These parades were done at the request of the Buick Motor Company in return for their sponsorship of the trip. At each stop, the local press was informed that the Michigan Marching Band traveled courtesy of the local Buick dealer. Band member, and Navy veteran, Bill Upton recalled sitting on a curb in a small town in Kansas resting his feet. Behind him was a shoe store with a sign in the window which read "Are Your Feet Tired?" Bill and the members of the band lamented, "If they only knew!" For the members of the band, it was a tedious journey filled with too many parades and rehearsals.

Not everyone in the Michigan Marching Band went on the trip. Some of the older veterans had family obligations and did not want to leave their families on Christmas Day. Revelli was forced to fill out the vacancies with three or four musicians who were not in the band. One was a faculty member, William Stubbins. Another was a graduate student, Allen Britton--who one day would become the Dean of the School of Music. Somehow, the student newspaper in Columbus, Ohio got wind of this and announced that the "great Revelli" had hired professional musicians from Detroit for his Rose Bowl Marching Band. This news nettled Revelli exceedingly.

At some point, during the long train trip, the band members had a "democratic" vote to decide if they were willing to march in the "infamous" seven-mile Tournament of Roses Parade that preceded the football game. With a band composed of so many World War II veterans who had their fill of marching parades during the War and with all the parades performed en route to California, the vote against marching the parade was predictably overwhelming. They told Revelli that they were "intensely interested" in conserving their energy so that they would be at their best for the "terrific" halftime show they intended to present. William Revelli was not impressed by this logic. Also, when word leaked out to the press that the band would not march the parade, Revelli received a lot of criticism. At one of the rehearsals held during one of the train stops, Revelli "politely" asked the band to vote again. Hovering over the band on his high platform, Revelli said, "Those willing to march, go stand on the goal line. Those opposed, stand in the end zone." Very few dared to stand in the end zone. The majority of the band yielded to the pressure to comply with the obvious wishes of the "Chief". Glaring at the handful of men standing in the end zone, Revelli uttered one of his famous "Sheesh!" sounds and mumbled "Rebels!" As it turned out, most members of the band found that marching and playing the Rose Parade was a beneficial warmup to the pregame and halftime performances at the game.

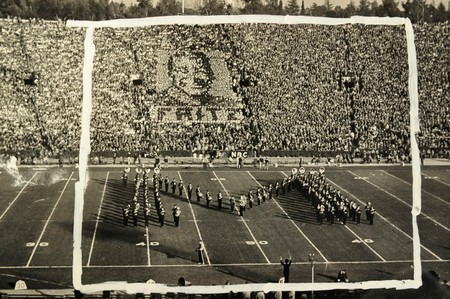

In her well-researched thesis, The History of the University of Michigan Marching Band, Regina Naomi Kane provides a detailed and invaluable description of the band's pregame and halftime performance at the 1948 Rose Bowl. On that day, the Michigan Band performed before a crowd of 93,000. It was the biggest crowd to see the Michigan Band in its history. On the field, leading the 131 members of the Michigan Marching Band was Drum Major, Noah Knepper. The game was broadcast on a local television station in Los Angeles only to be seen by the very few people in the city who owned a television. The broadcast had no sound—just the picture.

From Kane's thesis, we learn that the pregame show began with a fanfare at the North goal and was followed by a precision downfield drill to The Victors, and a drill routine to Sousa's El Capitan with the band's "grandiose high step" on full display. Next, the band saluted the University of Southern California forming the letters, USC, while playing California Here I Come. Then, the band marched into a MICH formation and marched to the South goal playing Varsity. A countermarch followed to midfield with a flank off to the sidelines.

The Michigan Band's halftime show was entitled Happy New Year with formations that reflected the major holiday or theme of each month of the year. For the month of March, the band formed a shamrock and played When Irish Eyes Are Smiling. In the shamrock, the band danced a jig to the tune of The Irish Washerwoman. For April, the band formed an umbrella and played April Showers. The theme for June was a wedding; July, a firecracker for the Fourth of July, etc. The highlight of the show was October—Halloween. Of this, Kane wrote:

The atmosphere got very spooky as the band played Misterioso and suddenly appeared as some huge skull and crossbones. As the band played Dry Bone, the skull chuckled to himself and rolled his eyes.

The Michigan Daily reported: “Michigan’s colorful marching band, composed of [sic] 128 precision drilled members, stage a brilliant array of high stepping antics…that never before have been seen in either the Rose Bowl or Michigan Stadiums.” To many in the crowd, it was the first time that they saw a high-stepping marching band, and they loved it. California sportswriters lamented how the Michigan football team crushed the USC Trojans. And some made the same comparison between the two bands. "And if that ain't bad enough," one sportswriter said, "the Michigan band comes out there at halftime and beats the USC band to death. Michigan trims 'em in music as well as football, so I quit."

After the game, the band left California aboard a special Southern Pacific train. Again, at the behest of the Buick Motor Company, stops were made en route to Phoenix, Tucson, and Kansas City where the band performed more parades and concerts. On the return trip, the band members seemed to have a lot of fun. There is a picture of some of the men, just hours after the Rose Bowl victory, in the smoking car with bottles of beer wearing their band caps backward. At the stop in Tucson, a "posse" of band members dressed in cowboy hats corralled the "bad guy", Revelli, and put a hangman's noose around his head.

The Michigan Marching Band returned to Ann Arbor on January 4 amidst praise and acclaim. President Ruthven was pleased with "the excellent playing and marching of the band." But not everyone was happy with the band's new marching step. The day after the Rose Bowl, President Ruthven received a letter from Maxson Judell, an alumnus of the University of Wisconsin. Judell was upset with the Michigan Band’s awkward looking high step. “I am 1,000,000% against such goose-stepping. That belonged to Nazi Germany—not to Michigan.” This criticism pointed out the one flaw in the new marching style that the Michigan Band tried to adopt. While the band marched to faster tempos and executed the high step, they retained the old military 30-inch step. This long step made the high step extremely difficult to do, especially at faster tempos.

Revelli knew that more had to be done to take the Marching Band where it ought to be. Over the winter months, he and Harold Ferguson had serious discussions about the Marching Band. In the President’s Report to the Board of Regents in the summer of 1948, reported that Harold Ferguson had “resigned” as the Assistant Director of Band and would “assume a full-time teaching assignment in the Wind Instrument Department of the School of Music.”

This development plus several other curious things that occurred over the next several months had significant implications for Revelli and indirectly the Michigan Marching Band. (But that is a story for another time.)

It was late summer in 1948, and Revelli did not have anyone to take charge of the Marching Band. He decided to seek out the person who was responsible for all the innovations in the Ohio State Marching Band. Revelli learned that the person he was looking for was a man named Jack Lee. Much of the transformation of the OSU Band was devised by Lee when he was a student at Ohio State. In the summer of 1948, Lee was a high school band director in Ohio. It didn’t take much convincing for him to accept Revelli’s invitation to come to Ann Arbor. When Jack accepted the position as Assistant Conductor, he was 25 years old—about the same age as many of the men he would lead in the Michigan Band.

The Michigan Marching Band would never be the same again.