Banding Together: Author's Edition

Banding Together: Author's Edition

by Jenn McKee '93

A version of this article originally appeared in the Michigan Alumnus magazine. What follows is the author's full version.

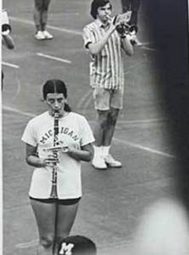

In the fall of 1972, the ranks of the Michigan Marching Band (MMB) significantly changed just after the passage that summer of Title IX. Twelve women got their first opportunity to don an MMB uniform and join their male counterparts on the field, with instruments, flags, and batons firmly in hand. But what should have been a shining moment for these new female members was undercut by having to perform “The Stripper” during their first halftime show in the Big House. What’s more, the formation for the song was a woman’s hemline, rising higher and high-er, as the crowd was encouraged to cheer.

“It just felt like such poor taste,” remembers Lynn Hansen, ’75, MA’77, who played tenor sax in the MMB that year. “I remember most of us women not feeling very swell about that. But there was this thinking, ‘Don’t make waves. We’ve got to make this work. We can’t be whiners.’”

Though U-M’s music school had officially struck down the MMB’s “males only” policy a year earlier, in 1971, nearly all Big Ten marching bands held firm to their no-female tradition until Title IX – which stated that “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance” – was enacted in 1972. (The University of Illinois Marching Band was among the first to convert, integrating 9 women to their ranks in 1971.)

For many, including U-M, this tradition stemmed from the band program’s historically close ties with Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC). From 1927 to 1934, Nicholas Falcone helmed U-M’s band, and during his tenure, ROTC faculty members supervised the band’s drills. This was the all-male military band culture that legendary MMB director William D. Revelli inherited when he took over in 1935, and it firmly remained in place until after his retirement in 1971.

But Revelli’s successor, longtime MMB assistant director (and former Marine) George Cavender, doesn’t appear to have been quick to accept the U-M music school’s new openness to the idea of having women in the ranks, either.

Archived articles from The Michigan Daily and The Ann Arbor News stated that an undated memo made the music school rounds in the summer of ‘71, re-emphasizing that “marching band is required of all male students.” Male music students who were physically incapable of marching, as well as female music students, were often placed in a concert band class that was in session during marching band rehearsals. (Cavender, in the press, argued that the memo was circulated before July 1, and that his department couldn’t afford to distribute an updated memo.) In addition, counselors weren’t alerted about this policy change (“I saw no reason to have done that,” Cavender told The Michigan Daily).

Press stories from this era mention that men who weren’t up to the physical demands of the band, as well as women, were regularly placed in an “alternate section,” but MMB historian Richard Alder – a clarinetist, equipment manager, and Kappa Kappa Psi President during this time of transition – has argued that no such “alternate” system was in place.

Despite being put off, some women pushed for an audition in 1971. Some were simply told there were “no spaces open.” And the first woman ever granted an MMB audition, Kathleen Gilroy, was initially told she’d missed the audition deadline, according to an Ann Arbor News article published in September 1971. A few weeks later, a male friend of hers told her he had an upcoming audition for the group, so Gilroy made more calls to Cavender’s office, pressing for a chance.

“I think Mr. Cavender is really upset by all the publicity that has resulted,” Gilroy told The Ann Arbor News. “Before the audition he barely even spoke to me, but afterwards, he kept explaining how ‘physical’ an activity marching was. And he made several references to all of the harassment he has gotten from reporters and women’s liberation advocates. I personally wasn’t trying to prove anything. I just enjoy marching and wanted to be in the band.”

Cavender told The Michigan Daily in 1971, “[Marching band’s] more violent physical activity than would be proper for a lady. It would be too hard – we couldn’t excuse a woman from rehearsals if she had ‘female problems.’ I certainly don’t excuse any of my boys from practice.” A campus protest, starring a women’s “band” – with tambourines and trash can lids – brought more attention to the issue.

So while women were technically eligible to march in the band beginning in 1971, none got a real chance to join the MMB’s ranks until Title IX forced the issue the following year. But Carolyn Good Kibbe – one of the 12 women admitted that historic season (9 wind players, 2 flags, and a twirler) – still faced push back at her campus audition, when she was told the band wouldn’t have flutes or piccolos in its ranks.

“I said, ‘What can I play?’ and I learned they needed alto horns,” said Kibbe. “ … I found and bought a used alto horn in a music store in Plymouth, and I took lessons with my high school director to learn to play it, and I went back and auditioned at band camp, the week before school started. I got fourth chair out of nine. … When I got the acceptance letter, … I ran around the block, I was so excited. … Also, they did march four piccolos in the block that year, but they were boys.”

Hansen, also part of that original class of MMB women, had been among those who’d fought to get an audition the previous year, only to be told she’d missed the deadline. When she auditioned in ’72, she not only made it, but had the strongest musical audition in her section, making her one the band’s first female section leaders.

“Just being in that uniform was huge,” said Hansen. “I’d seen my junior high school director in one just five or six years before that, and it just meant the world to me to join that tradition.”

Cavender had had to accept this change, telling The Michigan Daily in July 1972, “When a tradition denies a person his basic rights, then that tradition is made to be broken. I owe every qualified student an opportunity to play in the band if he wants to.”

Yet the newly coed band’s first halftime show included “The Stripper,” and that hemline formation. It’s hard to dismiss the sense that a not-so-subtle message was being sent.

Some argue, however, that the choice wasn’t a deliberate jab. “I think George just thought it was funny,” said longtime band announcer Carl Grapentine, who noted that this was just one small part of a larger show. “ … I don’t think he was trying to shame the first women in the band.”

As for the young men in the MMB’s ranks, there were a handful who seemed resistant to the change, but most accepted it and welcomed women into the organization. “From my experience in the block, the guys were fantastic,” said Hansen. “They were really supportive, they were collegial, and they would help if you needed it.”

“All the guys in the alto horns were great,” said Kibbe. “Not one of them harassed me for any reason. … But we had to go to Harris Hall to get our uniforms, and I remember walking there with other band members, and some older guys were behind us, and they kept saying things like, ‘You won’t make it,’ ‘This is too tough for you,’ and other things more along the lines of things you probably couldn’t print.”

Alto horn player Sally Weaver, also part of the MMB’s first class of women (and just 17 upon joining), came from Virginia and hadn’t previously been aware of the MMB’s all-male history.

“I remember vividly a sousaphone player glaring me down, like, ‘You shouldn’t be here!’” said Weaver. “ … We did something called a step forward back turn, and he would do that, staring me in the face and replacing the words with curse words. But it had no effect on me. I would just giggle. … It cracked me up.”

But again, most MMB members seemed to accept the change with grace. “When [Cavender] stood in front of the band on September 3, 1972 and said there would be women in the band that year, there was no audible response,” said Alder. “We believed what he said. … Possibly some had resentment, but there was no loud outcry that I ever heard. No one quit, that I am aware of. George’s insistence on continuing as we always had, in a gender-blind fashion, kept us believing.”

Of course, some things still left the women wondering how welcome they really were. The blue-prints for Revelli Hall, which began its construction phase in the fall of ’72, were never changed to accommodate an influx of women, but instead called for a tiny bathroom, with just a couple of stalls, “for visitors.” But then Cavender repeatedly asked Kibbe to speak to Rotary clubs about her trailblazing role in the MMB, and the women’s memories of their time in band are overwhelmingly positive. Many of the women got to travel to perform at Super Bowl 7 that first year, played at the Rose Bowl; Kibbe remembered having instrument polishing parties and dinner with her section on Friday nights; and Hansen still basks in memories of inter-band collegiality, rushing out of the dark tunnel and into pregame formation, and playing “M Fanfare.”

“It still gives me chills, just talking about it,” said Hansen.

“In typical George fashion, by the fall of ’72, he was bragging about how forward thinking and progressive he was, flipping on a dime and puffing out his chest about how he was responsible for women being in the band,” said Grapentine. “ … I think he thought, ‘Well, this is the way it’s going to be, so there’s no reason to drum out these first five or six.’ So give him some credit for that. And he never publicly cast aspersions on them.”

“Once you made it, I think [Cavender] considered you all aboard as a band member,” said Kibbe. “ … As long as you didn’t cross him on basic rules for any reason, he had no problem. Once we were in, he didn’t see it as a bad thing, I don’t think.”

The number of women in the MMB has grown through the years, and in 2001, the group was led by the first-ever female drum major, Karen England.

Which is to say, we’ve come a long way since 1972 – a time when, Grapentine confessed, “It took me a while to get used to seeing two people in band jackets walking down the street holding hands.”

Jenn McKee, ’93, is a former MMB trombone player and worked for more than a decade as a staff arts reporter for The Ann Arbor News. She is now a freelance writer whose work has appeared in numerous publications.